On a weekday morning in Jimma, before the city has fully shaken off the night’s mist, the clink of porcelain cups mingles with the low hum of conversation. Wooden stools scrape softly against tiled floors. A barista pauses mid-pour, listening more than speaking, as if the room itself is telling a story older than anyone inside it. This is Hirmata Coffee, a small business that opened its doors just last week in Jimma, Oromia. Yet in name, spirit, and intent, it is anything but new.

To step inside Hirmata Coffee is to enter a place where time seems to fold inward. The aroma of freshly roasted beans does not simply announce a café; it evokes memory. Long before Jimma became a zonal capital—before concrete, before corrugated iron—Hirmata was already a place of gathering, movement, and exchange. The café borrows the name deliberately, inviting that older story to speak again, this time through cups of macchiato, sacks of raw beans, and a quiet but deliberate effort to keep value close to where it begins.

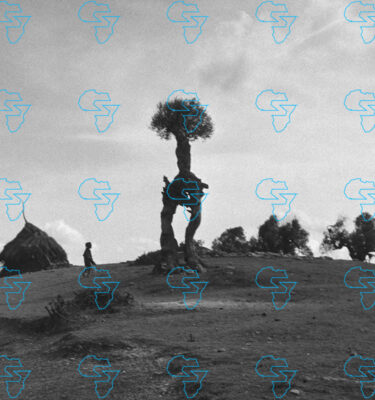

Hirmata was not originally a café brand, nor even a neighborhood in the modern sense. It was a market town—among the most important commercial centers in southwestern Ethiopia well before the nineteenth century. Positioned along long-distance caravan routes, Hirmata connected the highlands of Shewa and Gojjam with the fertile, coffee-rich regions of Kaffa and the Gibe states. Traders arrived on foot and by mule, carrying ivory, wax, hides, spices, and, increasingly, coffee.

At their height, Hirmata’s weekly markets were anything but modest. Tens of thousands of people converged there—Amhara merchants from the north, Oromo traders from surrounding regions, and groups from Omotic and lacustrine areas, including Kefa, Janjero, and Welamo. It was a place where languages overlapped, bargains were struck, and news traveled faster than messengers. Commerce here was not merely transactional; it functioned as social infrastructure.

From The Reporter Magazine

That economic importance placed Hirmata at the center of political history as well. When the Oromo Kingdom of Jimma—one of the five Gibe monarchies—rose in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Hirmata was integral to its expansion. Abba Magal extended control over the area, and his son, Abba Jifar I, consolidated power, building one of the region’s most formidable kingdoms. While Jiren became the royal and administrative capital, perched above the Awetu River, Hirmata remained the economic heart, beating steadily beneath the kingdom’s authority.

Even during the Italian occupation of the 1930s, when colonial administrators merged Hirmata and Jiren and expanded infrastructure along the Awetu, the commercial logic of the place endured. Roads, bridges, and administrative buildings came and went, but trade—especially coffee—remained the city’s lifeblood. Modern Jimma, in many respects, was built atop the bones of Hirmata’s markets.

It is into this layered history that Hirmata Coffee has now quietly entered.

From The Reporter Magazine

Jimma’s relationship with coffee is both a gift and a paradox. The region is synonymous with high-quality Arabica, cultivated in forested landscapes often described as coffee’s original home. Nearly every visitor leaves with kilos of raw, green beans—wrapped in plastic bags, destined for home roasting, gifting, or resale.

The tradition is a source of pride. But it also reflects a structural imbalance. Jimma produces coffee, yet much of the value generated from it—through roasting, branding, packaging, and café culture—has long been captured elsewhere, most notably in Addis Ababa.

For years, businesses like Hirmata Coffee existed primarily in the capital. They sourced beans from Jimma and surrounding areas, processed them, added value, and sold them back to urban consumers at a premium. Jimma remained, largely, a place of origin rather than transformation.

That is what makes the opening of Hirmata Coffee in Jimma quietly significant. It does not announce itself with spectacle. There is no excessive signage, no imported aesthetic. The space is modest: simple seating, restrained design, walls lined with coffee equipment rather than decoration. But beneath that simplicity is a deliberate business model—value addition at origin.

The café serves carefully prepared espresso-based drinks, but that is only part of its operation. Shelves display both processed and unprocessed beans. Customers can still buy green coffee, as they always have. Now, however, they can also purchase locally roasted, packaged, and branded coffee—produced in the same city where it was grown.

It is a small shift, but in Jimma’s coffee economy, it is a consequential one. It does not reject Jimma’s long-standing coffee culture; it builds on it, keeping more of the coffee’s journey—and its economic return—within the city.

Spend an hour inside the café and the clientele tells its own story. Young professionals work on laptops. University students argue over assignments. Older men debate politics over tiny cups of buna. Curious visitors drift in and linger. Conversations move easily between Afaan Oromo and Amharic, occasionally punctuated by English.

This, too, feels familiar.

Centuries ago, Hirmata’s markets were spaces of encounter—where regions, languages, and ideas met. The café recreates that function in contemporary form. It is not merely a place to drink coffee; it is a social node, where Jimma’s past and present negotiate their relationship.

Behind the counter, baristas move with quiet confidence, conscious that they are participating in something larger than a service transaction. Modern espresso machines stand beside traditional coffee implements, neither dominating the other.

Ethiopia often speaks of coffee as heritage, and rightly so. But heritage, when frozen in time, risks becoming ornamental. What Hirmata Coffee attempts—without fanfare or manifesto—is to make heritage productive.

By processing coffee locally and branding it with a name deeply rooted in Jimma’s history, the business advances a simple but pointed argument: tradition and modernity are not opposites. They are mutually reinforcing.

This philosophy reflects a broader, if uneven, shift underway across Ethiopia. In recent years, regional cities have begun hosting enterprises once assumed to belong exclusively to Addis Ababa—cafés, roasteries, and small-scale processors that resist being cast solely as suppliers to a distant center. Jimma, given its coffee legacy, is an especially fitting place for such a recalibration.

Naming a café “Hirmata” in Jimma is not a neutral act. It carries weight. It invokes a place that once drew tens of thousands of traders, anchored a kingdom’s economy, and shaped a city long before the city knew its own name.

The choice signals continuity rather than nostalgia. It suggests not a borrowed brand transplanted from elsewhere, but a return—an insistence that history can be resumed rather than merely commemorated.

Whether this model endures remains an open question. Small businesses in Ethiopia contend with familiar pressures: volatile prices, limited access to finance, supply constraints, and the rising costs of urban life. A café opening, on its own, does not amount to an economic revolution.

But social change rarely announces itself as one.

If Jimma’s residents begin to see roasted, packaged coffee as something that belongs naturally to their city—not as an import from Addis Ababa—then Hirmata Coffee will have achieved something quietly transformative.

Today, in a much smaller room, with polished tables and espresso machines, coffee moves from farm to cup within the same city. Stories pass between generations. History is not mounted on plaques; it is brewed.

As afternoon light filters through the café’s windows, a customer lifts a cup, inhales, and pauses before the first sip. It is an unremarkable gesture, easily overlooked. Yet in Jimma—in Hirmata—such moments are never only about coffee.

.

.

.

#Hirmata #Coffee #Jimmas #Market #Spirit #Finds #Life

Source link