Birhanu Lenjiso (PhD) is a distinguished Ethiopian sociologist, public intellectual, and policy practitioner whose work spans academia, research, media, and public service. A sociologist specializing in development studies, Birhanu has a wealth of experience teaching and working in academic institutions like Ambo University and the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI).

A co-founder and former deputy director of the East African Policy Research Institute (EAPRI), Birhanu has also held senior public office as the state minister for irrigation development in Ethiopia’s Ministry of Irrigation and Lowlands, where he contributed to national development planning and institutional reform.

A prolific author and influential thinker, Birhanu is widely recognized for his intellectual leadership and sustained contribution to debates on governance, development, and social transformation in Ethiopia. His recent book, ‘Bihertegninet’ (published in Amharic and Afaan Oromo) offers a rigorous reflection on nationalism, national identity, and self- determination.

In this interview with The Reporter’s Nardos Yoseph, Berhanu examines Ethiopia’s deepening political and social crisis through the lenses of governance, identity, and constitutionalism. He argues that Ethiopia’s challenges stem less from constitutional text than from the absence of constitutional culture and public ownership, cautioning against the assumption that constitutional amendment alone can deliver national cohesion.

From The Reporter Magazine

Berhanu also critiques the current National Dialogue Commission, while maintaining that national dialogue—despite its flaws—remains indispensable for addressing historical grievances and forging a shared political identity.

The discussion further explores the interlinked roles of transitional justice, elite pacts, and national dialogue, which Berhanu identifies as necessary political processes for Ethiopia’s stabilization, ideally sequenced to address historical injustices first. He also offers a regional perspective, warning that Eritrea’s influence in Ethiopia’s internal affairs is significant and strategically consequential, and stresses the need for Ethiopia to defend its national interests while avoiding unnecessary conflict. EXCERPTS:

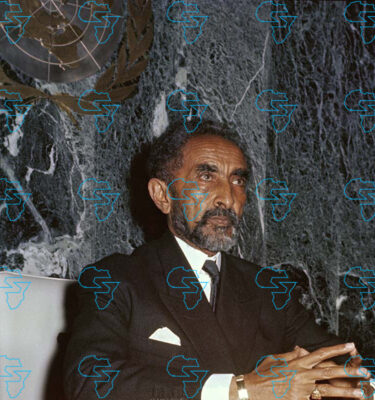

The Reporter: If we look at Ethiopia over at least the past 100 years—during the reign of Emperor Haile Selassie, under the Derg, under the EPRDF, and now under the Prosperity Party—conflict is ever-present. What is driving the conflict?

From The Reporter Magazine

Birhanu Lenjiso (PhD): As you noted, if we look at least the past 50 years, we have witnessed the change of two or three different governments. Government change, in a sense, involves both a change of people and a change of system. When a system changes, the governance model, the constitution, and ideology also change together. In this country, everything changes, and it always starts from zero.

When we ask why this keeps happening, for example, when the Derg overthrew the imperial system—whether through revolution or force—the reason was that the imperial regime failed to respond to public demands in an institutional and systematic way; it was exploitative. The Derg came to power claiming that it would create a system that served the people and would respond to their demands.

So, what were the public demands that had not been addressed? Primarily, during the imperial era, one was the land question, and the other was the question of ethnic equality. Many people often present these as two separate issues. But for me, they are not two questions—they are one.

Why? Because the land question is an expression of the ethnic question, or the question of representation. At that time, the grievance was that because land tenure systems differed between the north and the south, a top-down system imposed its own officials and took away people’s rights. Land, by its nature, belongs to a people. It is held collectively by different peoples. Therefore, the grievance was that one group took our land through its appointed administrators, and that land needed to be corrected and returned to its rightful owners.

So, the original question was not “land to the tiller.” It was essentially a “land for indigenous peoples” type of demand. In that sense, the question was one of managing diversity. When we stretch this argument further, it was fundamentally a demand to govern Ethiopia in a way that respects its diversity. In essence, Ethiopia had only one core question.

Over time, that question fragmented into two or three different demands, and as a result, the imperial system collapsed.

When the Derg came to power after the fall of the monarchy, it declared that there were two questions: land to the tiller and the nationalities question. It addressed land to the tiller through proclamation, and it claimed, in principle, to respect ethnic equality—but it refused to address that question legally and institutionally. As a result, the unresolved issue reignited conflict and produced ethnic liberation movements.

If we take the TPLF, EPLF, OLF, Afar, Ogaden—these were all liberation fronts. Many liberation fronts emerged, and ultimately, even with external factors involved, the Derg collapsed. The question that brought down the Derg was the question of identity.

By identity, we mean demands such as: recognize who we are; acknowledge that different nations exist within Ethiopia; give us representation. Even though the system changed, that question remained. Addressing it at its root required more than mere recognition.

Even if Emperor Haile Selassie or the Derg had said, “We recognize you,” the question would not have ended there. Recognition would have generated further demands. Some people say the TPLF brought the ethnic question to Ethiopia, but in reality, the ethnic question gave birth to the TPLF.

Because the ethnic question is fundamentally a question of representation, it precedes all others. When the EPRDF came to power, it stood on this question and established the federal system. In principle, the EPRDF appeared to provide an answer to what the people demanded. However, responding to that question alone was not sufficient, because it created new governance challenges.

Under the imperial system, there was no need for a shared narrative or negotiated agreement because the belief was that all peoples were one, governed through force. During the EPRDF era, once diversity was recognized, new claims emerged: we are many; we have differences and distinct interests; we want self-administration at the regional level.

Once that question was answered, additional issues arose—shared national identity, borders, division of power, and resource allocation. These are all sources of conflict. Resources are scarce. If we cannot agree on how to share them, and if the distribution mechanism does not satisfy everyone equitably, conflict becomes inevitable.

For example, one grievance during the EPRDF era was that the TPLF dominated power and monopolized resources. Today, similar grievances persist, with some claiming that the current government represents Oromo dominance or that a familiar cycle of political monopoly is repeating itself. Where does this come from? It comes from mistrust.

So, when diversity was not recognized, the source of conflict was the demand for recognition. Once recognition was achieved, conflict shifted to disagreements over the use of shared resources. Therefore, the main source of conflict in this country is the absence of a shared narrative about how we understand and manage diversity.

Conclusively, this problem can be interpreted differently at different historical moments—under Emperor Haile Selassie, the Derg, the EPRDF, and now the Prosperity Party—depending on public awareness. But a country can only exist when there is shared agreement and trust. Trust emerges only when we build a shared narrative.

At the bottom of this problem, the core issue is the existence of a profound narrative gap.

Critics say ethnic narratives heavily influence federal policy. What is your view on ethnic federalism and national unity?

Here, there is a problem of terminology. The reason is that in Ethiopia, a form of federalism built on the basis of nationalities has been established, and the Constitution itself speaks of “nations, nationalities, and peoples.” There are ongoing debates and questions about who exactly these “nations, nationalities, and peoples” are, and similar issues. Personally, I do not subscribe to these lines of argument.

When ethnic federalism was introduced, I believe it was done with the intention of making Ethiopia, as a country, a place where Ethiopian identity, diversity, plurality, and federalism could coexist as an ideal model of governance. I am of the view that there is no better system of government for Ethiopia than federalism. The question that follows is not whether federalism is appropriate, but rather how it should be structured.

This is not something that one can simply wake up one morning and decide arbitrarily. The structure must be determined by the demands coming from the people themselves. As is well known globally, federalism can be structured in only two ways: one is on a territorial basis, and the other is on the basis of identity. In Ethiopia today, there is a widely held position that organizing federalism along territorial lines would be preferable. But the critical question is: has the public demanded such a structure?

Have the people asked for a territorially based federal arrangement? Take the former Southern region as an example. Because of limited resources and relatively small population sizes, fifty-six ethnic groups were grouped into a single regional state and administered together. Over time, however, demands began to emerge, and today we can clearly see that these groups have moved toward forming separate regional states. This demonstrates that unless the people themselves demand territorial organization, what right does Ethiopia’s political elite have to sit down and decide, “This is what is best for you”? Where do they derive that authority from? On what basis can they claim, “This is what you want”?

I say this with confidence as a researcher who specializes in this area. Even at the level of conceptual clarity alone, I believe this issue has caused significant suffering to many people. I do not choose on behalf of the people. If the people say, “We want to organize ourselves based on our identity; this identity is the basis of our historical marginalization; and this is how we want our demands to be addressed,” then who am I to say, “No, organize yourselves territorially instead”? That is where the fundamental problem lies.

Secondly, even the current Ethiopian federal system itself has not been organized in the way the people actually demanded. Why? Because under what might be called a “tyranny of numbers,” arguments such as “you are small,” “you lack resources,” and “your population is too limited” were used to group many peoples together. As a result, regions such as South West Ethiopia, South Ethiopia, Central Ethiopia, Benishangul-Gumuz, Gambella, as well as Oromia and Amhara, are all nationality-based regions that encompass a very large number of ethnic groups. These regions, in practice, are also structured largely along territorial lines rather than strictly ethnic ones. So both logics coexist within the system.

Ultimately, even if the administrative structure is arranged in that manner, as long as the people living within it continue to define themselves by their ethnic identity—and as long as that remains their demand—there is nothing wrong with that. There is no problem with people expressing their identity. There is no problem with people governing themselves. Let them express themselves; let them administer themselves. Let us leave matters that concern them to them.

As intellectuals and as a society, our responsibility should instead be to focus on building a shared national project. If the Oromia region chooses to promote its culture in the way it sees fit, as long as it does not infringe upon others; if it chooses to administer itself through the Gadaa system; if it chooses to write in Qubee—these are its own affairs.

What we should be discussing collectively is how to build Ethiopia as a federal country in a way that treats all nations, nationalities, and peoples equally and fairly; how to strengthen the federal structure; how to improve the federal system; and how to construct a shared national narrative. Sitting in one place and speaking on behalf of others is not a path toward reconciliation—it is a path toward further division.

For instance, some non-Oromo elites argue that Afaan Oromo should be written using the Ge’ez script. Who asked for that? When did the people say, “Please change this for us”? This kind of thinking—that one can simply wake up and decide to change something the people did not ask for—reflects the same coercive mindset that existed in the past. Instead of offering opinions on issues and spaces where one was neither invited nor consulted, it would be better to work on genuinely shared national concerns.

What is particularly troubling is that the shared national space itself is a vacuum; there is nothing there. Almost nothing is being done in that space. In the current reality, issues related to regions and ethnic groups have gained strong ground and visibility. Every ethnic group loves its culture, wants to nurture it with care, and wants to see it flourish. That does not require much external support—it happens naturally.

Where we are struggling is in building a shared national project. Over the past 27 years, since ethnically informed federalism was introduced, everyone has focused inward, on their own group, and as a result, there have been weaknesses in building a common national framework. That said, this was not strong even before. Under Emperor Haile Selassie, the focus was on the monarchy, not on building an inclusive national identity. The Derg, likewise, was preoccupied with Marxism-Leninism rather than constructing a shared Ethiopian identity.

When I say this, I am not suggesting that we lack the raw materials to build a national identity. On the contrary, we have very strong foundations. Compared to many other countries, Ethiopia has rich resources for building a shared national identity. Our understanding of freedom; the idea of Ethiopia as the cradle of humankind; our identity as the birthplace of coffee; the fact that Ethiopia’s diverse regions and peoples are sources of civilization; northern Ethiopia’s architectural heritage; Axum’s trading civilization; the Oromo Gadaa system—all of these have immense value in bringing people together.

If we focus on these shared elements and use them as the basis for building a national identity, we would be better off. At the same time, there should be restraint and ethical boundaries when one ethnic group speaks about another.

It has now been more than two years since the National Dialogue Commission began its work. Among political elites, one of the most controversial issues has been the national dialogue itself. Various long-established as well as recently formed political parties have publicly announced that they are distancing themselves from the dialogue. From the outset, critics argue that the process has been flawed; that it imposes limitations preventing genuine questions from being raised; and that the Commission was established primarily to advance the government’s narrative. How do you assess the performance of the Commission, and how do you view the arguments raised by those actors who have chosen to exclude themselves from the process?

I approach the idea of national dialogue and the manner in which the National Dialogue Commission was established, or is currently operating, by separating them into two distinct areas.

First and foremost, we need to reach agreement on the concept itself. Countries like Ethiopia, which were formed through coercive force, can only address and heal the historical scars they have suffered through this kind of political process. That is how all countries have gone through such experiences. The wounds they have endured, or the painful paths they have traveled, are addressed by passing through such a process.

The National Dialogue Commission should have been established much earlier; it has been delayed for a very, very long time. Now that the opportunity exists, my belief is that we should view it very positively and move forward by adapting it to the realities we are currently facing. Therefore, at the first level, we must agree on the necessity of the concept itself.

Because this is something that has never been attempted even once in our country before, we must accept that moving forward by filling gaps and making corrections along the way is essential. Once I state this as a principle, then yes—there may indeed be shortcomings in the way this national dialogue has been established.

For example, someone may stand up and say, “This does not represent me.” The next logical question would be: “Then who represents you?” I do not believe that such a person would actually present someone who truly represents them. In the current Ethiopian reality, it is not easy to reach agreement on anything. Even agreeing on the question of what Ethiopia is—let alone agreeing on individuals who are selected or appointed—is extremely difficult.

Beyond that, everybody has the opinion that nobody represents them. I do not believe that it is possible to select a commission that satisfies everyone. The core issue being raised in the context of the dialogue is something that has existed even before, including during discussions surrounding the Constitution.

When the Constitution was drafted, there were those who said, “I was not represented.” When we respond by saying, “A representative from your own community participated,” the answer we receive is, “No, that person does not represent me.” So who represents this person, then? Until that individual himself appears, he will never say, “I am represented.” This is the kind of problem the country is grappling with.

Given such deep confusion and complex problems, how is it possible to conduct a dialogue that is credible and trustworthy?

I have said this before, and I will say it again: if it were possible, the National Dialogue Commission perhaps being run by artificial intelligence might even be better. It could potentially help resolve the problems Ethiopia is facing today. But even then, one group could manipulate it, so it might still be said that it would not work.

So, in my view, we must first agree on the idea that national dialogue is the only viable hope for Ethiopia—an option for which there is no alternative. We must agree on the idea that it plays a significant role in reconciling a grievance-filled politics where, for 150 years, people say, “Someone killed me, oppressed me, wronged me,” as well as another kind of politics that is obsessed solely with the past and struggles to move forward rather than backward.

Once we agree, in principle, that national dialogue is necessary, then yes, it will not be perfect. There may be shortcomings at the level of representation, inclusiveness, human capacity, and lack of experience. For instance, there were criticisms saying, “How can a national dialogue be conducted without the elders of the country?” But national dialogue is not traditional elder mediation, nor is it political bargaining, nor is it simply conflict resolution.

What is called national dialogue is a political process. It is a pathway for countries with complex, multi-layered problems to arrive at lasting solutions by listening to and deliberating on all demands and grievances, and by building a shared narrative and identity. Only if we accept this, and only if we strengthen and support the commission that has already been established to the extent possible, can this process succeed.

Beyond that, there can be no commission that perfectly represents everyone without gaps. I do not believe that such a commission can be established in Ethiopia under current conditions.

The Commission’s leaders have repeatedly stated, in various public forums and discussions with citizens, that one of the key issues raised is the revision of the Constitution. What is your stance on this? Is it truly possible to create a national consensus through constitutional amendment?

I also view this by dividing it into two areas. Just like the National Dialogue Commission, I do not believe that the Constitution is something everyone either loves unanimously or hates unanimously. Our Constitution has gaps. The Constitution itself contains provisions that allow for amendment.

In principle, if a person raises a question in a sound and logical manner, the Constitution can be amended. Moreover, as a matter of fact, I believe the Constitution has already been amended about two times—many people are not aware of this. For example, it was amended to address overlaps between elections and population and housing censuses.

Amending the Constitution is not as difficult as it is often portrayed to be. However, in relation to our current situation, what I often see as a major problem is the issue of conceptual clarity. For instance, there are people who ask: what exactly do “nation” and “nationality,” as stated in the Constitution, mean? In this regard, it is true that there is a gap.

The Constitution presents “nation” and “nationality” almost as the same thing. Yet, technically, “nation” refers to a group, while “nationality” refers to an individual. However, there is a common interpretive approach that says, for example, “nation” means Oromo and “nationality” also means Oromo. But that is not what the Constitution’s content actually implies.

There are other valid issues raised regarding other articles as well. In principle, anyone can raise a question, use the properly established provisions, follow the constitutional process, and amend it.

In the past, constitutions that were rigid and inflexible—unable to adapt—ended up being discarded when questions of amendment were raised. Therefore, there are criteria that must be fulfilled for amendment; if those criteria are met, then amendment should take place. That is what I believe.

Does amending the Constitution really, as some argue, make it possible to create a national consensus and strengthen national unity?

In practice, how many Ethiopians actually know the Constitution? How many of the articles in the Constitution are, in fact, perfectly crafted—there are many. The core substance of the Constitution, by the way, lies in its provisions on democracy and human rights. And yet, in our country, we see these rights being violated in so many ways. Both the government and the public have existed in a condition where the Constitution is largely unknown.

Many people, for example, raise Article 39—the right to self-administration up to secession—as a major loophole and problem. But tell me: have any people actually seceded because that article exists in the Constitution? I would argue, rather, that because it exists, more people have not seceded. In Ethiopia, the number of people who deeply understand the content of the Constitution and actively use it is very small.

In Ethiopia, I believe there is a Constitution, but I do not believe there is constitutionalism. Therefore, while familiarizing ourselves with the Constitution and improving what we want to improve is a good thing, raising the question of constitutional amendment—and even amending it—in a country where constitutionalism does not exist will not resolve the fundamental gap at its root.

Just as changing systems of government has not been able to eliminate conflict, I do not believe that amending the Constitution alone can strengthen Ethiopia’s unity. However, in principle, I do believe that there is nothing wrong with amending it.

Earlier, you mentioned polarized and extreme positions. There are arguments that, given the grievances, injustices, and human rights violations different communities claim to have suffered at the hands of one another or various political forces, a transitional justice process must be completed before a national dialogue. What is your stance on this? Do you agree?

I do not believe that, necessarily and sequentially, one must strictly come before the other. At the same time, I also do not believe that if one precedes the other, it is necessarily a bad thing.

There are three things Ethiopia needs.

The first is transitional justice. Transitional justice is necessary because there is a historical grievance in this country. Those who were wronged by state power in the past must be compensated; the harms committed against them must be acknowledged. There are communities that demand recognition, memorials, and acknowledgment of the injustices they endured. Some of these demands may arise from political motives, while others stem from genuine experiences.

This is where a Truth and Reconciliation Commission comes in—separating what is true, officially acknowledging that “yes, this injustice did occur,” and then closing that chapter with a collective commitment to ensure that similar abuses do not happen again. That is what closing a chapter means.

So transitional justice is a necessary political process to close historical injustices and move forward together.

The second is what our elites often refer to as an elite pact or elite negotiation. In Ethiopia, this usually comes up in the context of calls for a transitional government. Just the other day, I heard someone in the media saying that while they were fighting for a transitional government, they missed the election.

I think elite pacts are equally important in this country. Usually, the outcome of elite pacts is dialogue, negotiation, and power-sharing. If necessary, even outside electoral mechanisms, elites may negotiate and share power for the sake of national unity and public peace. Ethiopia’s recurring crises largely originate from elite behavior, so elite negotiations are necessary.

The third is what we call national dialogue, whose primary objective is often the construction of political identity—a shared political narrative and collective identity.

So which of the three should come first?

If transitional justice comes first, historical grievances are addressed, and both the aggrieved and the aggrieving sides move toward the center, resolve their issues, and meet there. After that, engaging in dialogue to build a shared national identity can be very effective.

Even now, agendas have been collected and discussions held in various places. What has been gathered needs to be sorted—what should be addressed through truth and reconciliation, what through dialogue, and what may require establishing other institutions. After that, they can proceed toward national identity construction.

As for national identity building, I personally believe it should be done in two phases. There is a form of national dialogue that should happen at the ethnic or national group level. Then, at the country level, there must be dialogue on how different groups—having resolved their internal differences—can coexist with others within Ethiopia.

This approach makes the process easier. Otherwise, take Oromia today: there are many different forces and many competing interests. One group says, “I want to live within a democratic Ethiopia.” Another says, “I want secession.” If these groups first talk among themselves and resolve their differences, then any agreement reached at the national level will have a higher chance of acceptance when it trickles down and of gaining legitimacy among the public.

So three processes are required. Sequentially, for me, if transitional justice comes first, it creates a favorable environment for compromise—that is my belief.

Many argue that Eritrea’s influence cannot be ignored, whether in relation to Ethiopia’s internal cohesion or Ethiopia’s relations with its neighboring countries. What is your view on this?

For me, Eritrea is still a part of Ethiopia. Indeed, in principle, it says, “I have seceded,” but even when it seceded, it was not really for the purpose of secession. Even now, it has not truly seceded. The reason is that Eritrea continues to involve itself—actively and continuously—in Ethiopia’s internal affairs. It operates and intervenes in our internal politics; it inserts its hand into our domestic political processes and remains present there.

Secondly, Eritrea itself was constructed as an Ethiopian buffer zone. I believe it was created both to neutralize Ethiopia’s interests and, at the same time, to serve as a platform from which influence can be exerted on Ethiopia. That is how I understand it.

I also believe that there are other powers that drive and steer Eritrea. These countries have played a significant role by using Eritrea either to confront Ethiopia directly or as a tool to exert pressure on Ethiopia. I am convinced of this.

Because of their interest in Ethiopia’s natural resources, these countries have fashioned Eritrea into a buffer zone and use it to create internal instability and turmoil within Ethiopia. I view Eritrea as a launching ground—a staging area that others use to attack or undermine Ethiopia.

How should Ethiopia navigate this situation?

Eritrea does not pursue or safeguard its own national interest. It does not have a self-directed, solicited policy of its own. Its people fought for thirty years to gain independence, and yet that independence has now been squandered over another thirty years.

Eritrea is Egypt’s Trojan horse.

Beyond that, Ethiopia has repeatedly stated that it does not seek war. However, safeguarding national interest also includes the use of force. Therefore, Ethiopia should not restrain itself from going that far if it becomes necessary.

.

.

.

#Dialogue #Constitutionalism #Identity #Birhanu #Lenjiso #Reflects #Ethiopias #Deepening #Political #Social #Crisis

Source link