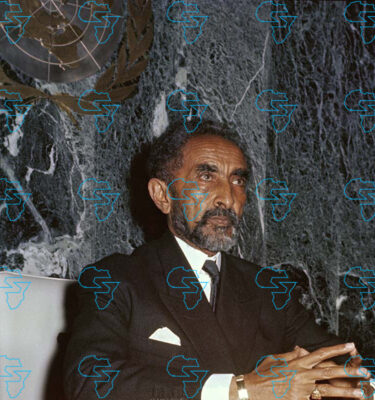

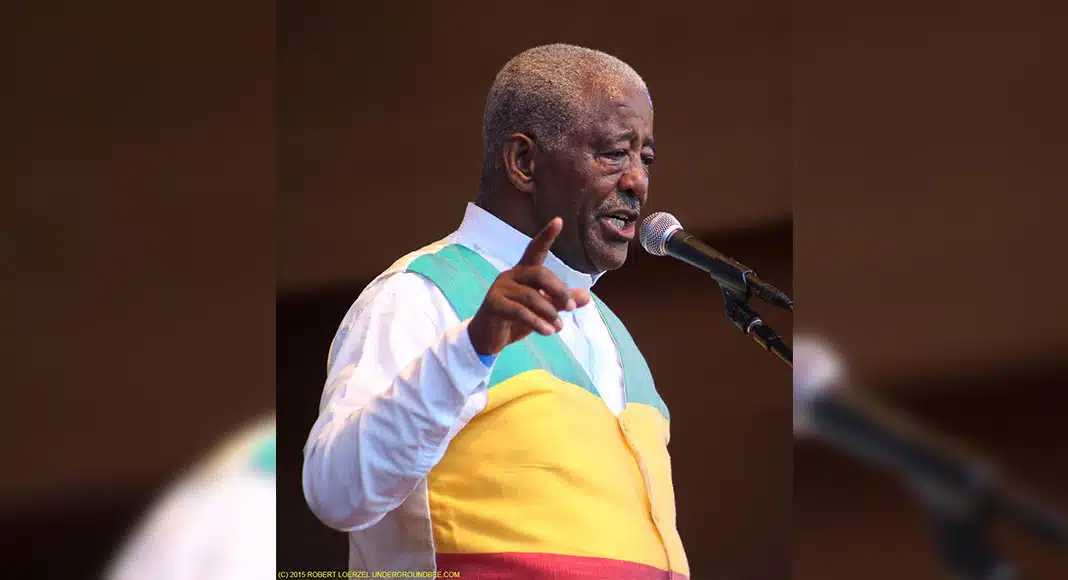

Mahmoud Ahmedan iconic name etched in the annals of Ethiopia’s musical history. Born on May 8, 1941, in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, Ahmed transcended from a humble shoe shiner to a revered singer and performer, remaining an indomitable figure in Ethiopian music. Crediting his revealing journey from the city streets, working odd jobs, to his first professional singing at the Arizona Club, his story is just as captivating as his music. Throughout his career, he lent his voice to several prominent bands, and even delved into business by opening his own music store. As his fame spread beyond Ethiopia, Mahmoud Ahmed’s career experienced a resurgence in the late 20th century, propelling him onto the international stage. Join us as we explore the life, struggles, and accomplishments of this trailblazing Ethiopian musician.

Early Life and Background

Family and Ancestry

Mahmoud Ahmed, a prominent Ethiopian musician well-known for his soulful voice and vibrant performances, was born on May 8, 1941. Born in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, Mahmoud is of Gurage ancestry. Despite coming from a family with no musical background, his passion for music was evident from an early age.

Growing up in Ethiopia’s capital city, Mahmoud showed no inclination towards conventional career paths, single-mindedly pursuing his love for music. From the barefoot boy who shined shoes to the adored artist on the stage, Mahmoud Ahmed’s journey is a testament to his resilience and undying passion for music.

Growing Up in Addis Ababa

Raised in the bustling city of Addis Ababa, Mahmoud’s engagement with music began early in his life. Even as a boy, his love for rhythm found him tapping his shoes to the beat, creating an ambiance of creativity that surrounded him. Even when faced with challenges, his inherent love for music served as an escape, helping him get through life in the busy city.

Initial Employment and Challenges

Leaving school unqualified, Mahmoud began his professional life quite early. He embarked on his journey as a shoe shine boy, hungry to make an end meet in the vibrant yet challenging city of Addis Ababa. Nevertheless, his life took a significant turn when he landed a job as a handyman at the Arizona Club. This period in his life introduced him to new opportunities, seeding his initial days in the world of music.

Mahmoud seized the chance to sing at the club, marking the onset of his musical career in the early 1960s. The hardships he faced did not disparage him. Instead, these challenges shaped his commitment and dedication to his artistic journey, defining his path as an influential figure in Ethiopian music history. Over time, Mahmoud Ahmed found more than just a passion in music; he found his destiny.

Musical Beginnings

The initial phase of Mahmoud Ahmed’s illustrious career began with his first singing experiences at the Arizona Club, transforming him from a humble handyman to a budding performer.

First Singing Experiences at the Arizona Club

Working as a handyman at the Arizona Club offered Mahmoud Ahmed a rare opportunity to explore his latent talent. The bustling nightlife of the club allowed him to tune into the rhythm of Ethiopian urban culture and its rich musical heritage. Immersed in this vibrant atmosphere, Mahmoud’s life took a serendipitous shift. He got the chance to sing his very first song in this intimate setting in the early 1960s. At the time, there were famous local bands often performing in the club, granting him unique exposure and access to Ethiopian music’s versatile styles. His distinctive voice, honed by many nights in the Arizona Club listening to various influential bands, marked the onset of his promising career.

Joining the Imperial Body Guard Band

Mahmoud Ahmed’s journey took a pivotal turn when he joined one of the most respected groups of that era, the Imperial Body Guard Band, in 1962. A prestigious music ensemble dedicated to the Emperor of Ethiopia, this band was a platform for musicians to showcase their talent to a wider audience. As one of the primary singers, Mahmoud’s unique sense of melody and passionate stage presence delighted both the band members and the audience. Mahmoud’s tenure with the Imperial Body Guard Band (which lasted until 1974) marked an essential phase in his career, contributing significantly to his distinctive musical style. It also earned him the recognition and respect of both his peers and a rapidly growing fan base.

Career Development and Collaborations

As Mahmoud Ahmed progressed in his musical career, he began recording with the famous Ethiopian record labels, Raw and And you. This period had significant influence on Mahmoud’s music and popularity as these labels were known for their significant contributions in promoting Ethiopian music across the nation.

Recording with Amha and Kaifa Record Labels

During the 1970s, Mahmoud Ahmed started recording with the Amha and Kaifa record labels. These studios were responsible for the spread of Ethiopian music during this era and encompassed various genres that merged traditional Ethiopian music with modern sound. Working with these influential labels allowed Mahmoud Ahmed the opportunity to leave an indelible print on the music scene of Ethiopia. His soulful voice and penetrating lyrics captured the hearts of many, leading to his rise as a prominent figure in Ethiopian music.

Performing with Various Bands

Throughout his musical journey, Mahmoud has shared the stage with various bands, each contributing to the richness and diversity of his music portfolio. He is known for his collaborations with the Ibex Band, Venus Band, Walias Band, Roha Band, and notably, the Idan Raichel Project.

Ibex Band and Venus Band

Mahmoud’s affiliation with the Ibex Band and the Venus Band played a significant role in shaping his musical style. His collaborative efforts resulted in unique rhythmic structures and compelling melodies, leaving a remarkable impact on the Ethiopian music landscape. His time with these bands enabled him to refine his performance skills and solidify his place in the musical world.

Walias Band and Roha Band

In addition to the above collaborations, Mahmoud Ahmed’s performances with the Walias Band and the Roha Band deepened his engagement with Ethiopian pop music. Both bands provided him with the platform to incorporate traditional Ethiopian rhythms with contemporary sounds, successful in drawing in a wider audience base.

Collaborarations with etds of Ricker Project

Mahmoud Ahmed also collaborated with the ADDAN Project Project. This project consisted of musicians from around the globe who contributed to a diverse and multicultural sound that resonated with a global audience. Music from this project was widely appreciated for its eclectic blend of cultural influences. This collaboration further expanded Mahmoud’s fan base, ensuring his music was enjoyed by people far beyond the borders of Ethiopia.

Entrepreneurship and Continued Success

Opening a Music Store in Piazza

In the 1980s, Mahmoud Ahmed, determined not to remain a mere spectator on the sidelines of the thriving Ethiopian music industry, ventured into entrepreneurship. His forward-thinking business acumen led to the establishment of a music store in Addis Ababa’s culturally rich district – Piazza. This was not just a commercial adventure, but also an endeavor to preserve and spread Ethiopian music locally and internationally. His store became a hub for music lovers and supported many young artists trying to establish themselves in the industry. The creation of this music store solidified Mahmoud’s imprint in the Ethiopian music scene beyond his singing and performances.

Musical Renaissance in Europe and the Americas

Since the late 1990s, Mahmoud Ahmed’s musical career has undergone a tremendous resurgence in popularity, echoing in the far reaches of Europe and the Americas. Thanks to Buda Musique, an independent record label based in Paris, which introduced the Ethiopiques series on compact disc, Mahmoud’s unique and soulful musical style gained a new international recognition. This series of reissues has played a significant role in the revival of Mahmoud’s music among a broader global audience. It infused new energy into his career and manifested itself in new recordings and concert tours. Mahmoud’s diverse and eclectic repertoire was warmly received by European and American audiences, allowing the authentic Amharic rhythms to reverberate in these new territories. This period saw Mahmoud, a renowned figure in Ethiopian music, extend his influence beyond the borders of his homeland, becoming a globally recognized voice of Ethiopian music.

Influence of the Ethiopiques Series

The Ethiopiques series, launched by Buda Musique, played a pivotal role in the revival of Mahmoud Ahmed’s career. This influential collection of compact discs that focuses on Ethiopian music had a significant impact on reintroducing Ahmed’s extraordinary talent to the global stage.

Impact on Revival of Mahmoud Ahmed’s Career

The launch of the Ethiopiques series in the late 1990s marked the beginning of a burgeoning resurgence in Ahmed’s popularity. Despite already having a successful career in Ethiopia, his music was relatively unknown to the broader international audience until the series brought his songs into the limelight.

The series featured a rich spectrum of Ethiopian artists, with Mahmoud Ahmed gracing numerous volumes. His distinctive vocal style and heartfelt lyrics resonated with the listeners, creating a newfound appreciation for Ethiopian music. Consequently, Ahmed’s fan base expanded beyond Ethiopia, fostering a new path in his career that led to international recognition and respect.

Collaborations and Tours with Either/Orchestra

Post the Ethiopiques series, Ahmed’s international presence was firmly established. His music began to cross borders, reaching a wider audience across Europe and the Americas. During this period, he cultivated a successful partnership with Boston’s Either/Orchestra, leading to a series of collaborations and tours.

The Either/Orchestra, known for its versatility and innovative approach, complemented Ahmed’s traditional Ethiopian rhythms, resulting in a harmonious fusion of cultures and sounds. The tours were a success, attracting audiences worldwide and further solidifying Ahmed’s position as an icon in Ethiopian music. These collaborations and tours have played a significant part in ensuring that Ahmed’s musical legacy continues to be celebrated and enjoyed by generations of music lovers.

In conclusion, the Ethiopiques series served as a catalyst, reviving Mahmoud Ahmed’s career and extending his influence far beyond the borders of Ethiopia.

The habesha

.

.

.

#Exploring #Musical #Journey #Mahmoud #Ahmed #Ethiopias #Revered #Singer #Habesha #Latest #Ethiopian #News #Insightful #Analysis

Source link