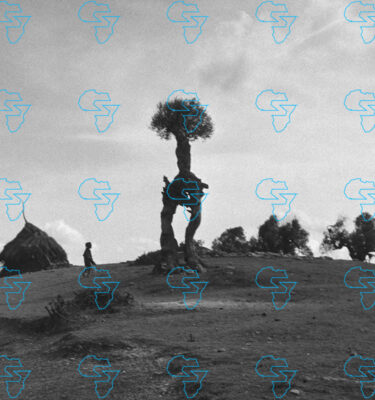

Across the small towns of villages of rural Tigray, displacement and illegal migration have become a grim reality for thousands of young people who see no future for themselves in the war-torn region.

Sources familiar with the crisis say it is deeply intertwined with human trafficking networks, political instability, and governance failures, leaving families desperate and communities destabilized.

“The situation related to displacement is very serious,” said Habtamu, a resident of the town of Mehoni in southern Tigray. He explained that in places like Adom, Raya Rayuma, or Raya Azebo, the displacement rate is dreadfully heavy.

“Every day many young people are fleeing the towns and cities. They are going illegally, mainly to Saudi Arabia,” he told The Reporter.

The costs of these perilous journeys are staggering, ranging from 100,000 to 250,000 Birr per person, according to sources.

A system known locally as Mejan, orchestrated by Arabic-speaking brokers, compounds the problem.

“If you bring three or four girls, then one man can travel without paying. This is how it works on the ground and that is why the migration keeps growing,” the source said, underscoring the structure’s entrenchment.

Local officials admit awareness but cite systemic challenges.

“Yes, it is true. The traffickers are very organized, but they are not well known. Many operate from Addis Ababa. Some of the ones who supply girls are based in a slum area known as Delala Sefer in Mekelle,” said a resident of Mekelle, who reports that his neighbors have yet to learn about the fate of their son after he chose to leave the country several months ago.

Families often pay additional fees at various stages of the dangerous migration process, covering everything from food to transportation with costs sometimes amounting to thousands of Birr.

“Our towns, especially those in rural remote areas, are full of stories like these. Because of poverty and hopelessness, parents and families accept sending their children abroad. The main problem is that the system to bring these illegal traffickers to justice and accountability is lacking,” said the relative of a migrant.

Brokers exploit banking systems to operate with impunity, using intermediaries and multiple accounts, according to sources.

“The banks know, but they won’t stop them without a court order. And that is the truth,” Habtamu told The Reporter.

Political Instability Further Exacerbats The Crisis. Mehoni and Surrounding Towns such as Alamata, ofla, and Raya Azebo facesbo face challenges.

“Because of politics, the zonal administration was overthrown. The legal administrative office was moved out, and the rest were pushed into the desert. Many young people have now gone into the desert areas; militias and security forces are moving around. It is truly a crisis,” said a resident of Raya.

Multiple armed groups, including the Tigray Defense Forces (TDF) and other unnamed entities, are allegedly contributing to instability.

“The TDF is supposed to be the Tigray Defense Force, meaning the force of the people of Tigray. But the current disintegrated behavior it is demonstrating makes it look like it is more occupied with pushing the agenda of one political party. That is not right,” said one resident.

Habtamu notes that local youth and other ex-combatants have been displaced repeatedly.

“Some have already gone into Afar. Others, after leaving earlier, have now regrouped again. Honestly, we don’t even want to see these people anymore — it’s repeated again and again. Repeated wars, repeated unrest,” he told The Reporter.

Security forces in Mehoni have also been criticized for acting outside their mandate.

“They are concentrated in the center of the town, intimidating the youth. Their operations are more about serving one political party than protecting the people,” said another of the town’s residents.

Local voices stress the need for dialogue and assessment.

“We need to sit down as a people, and assess the situation together. The assembly should review the war: its benefits, its harms, its outcomes. That way, we can identify lessons, resolve our grievances, and move forward. But until now, no such assessment has been done. That is what troubles me most — that we keep living through these repeated crises without ever learning from the last one,” said a resident of Mekelle.

The displacement crisis in Tigray, residents say, now rivals the devastation caused by war.

“Migration means leaving your country. Refugee means when you enter another country — when you are in someone else’s territory. But what we are seeing now is mass migration. And this is destroying us totally — destroying our citizens, destroying the country itself,” said Abel, a Mehoni resident.

Sources familiar with the matter told The Reporter that last year alone, 32 youths from a single woreda died attempting to migrate to the Middle East.

An expert familiar with migration data collected by the regional administration described just how serious the crisis is.

“Across 49 woredas, some 27,000 people have migrated in 2024 alone, often through irregular channels. Many of these journeys end in tragedy: drowning in the Red Sea, detention in foreign camps, or disappearance without a trace,” the expert told The Reporter.

A resident of Irob Woreda in northern Tigray described the heartbreak and sorrow they faced last year after losing a sibling to the waters of the Red Sea.

“There is not a single day without grief. We bury one brother in the morning, another one leaves for migration in the evening. We are losing a generation,” said the resident.

Brokers maintain extensive networks, identifying potential migrants based on desperation, family connections abroad, or financial capacity, according to the region’s residents.

“These brokers have a wide net. They study people, they identify those who are desperate, and then they push them. Migration is their business,” one local explained.

For many young Tigrayans, migration—whether legal or illegal—appears to be the only option.

“If you ask anyone — would you migrate if you had the chance? The answer is yes. Because here there is no assurance of sustainable safety, no finance, no stable governance, no opportunities. Most of the youth is ready to leave,” a source said.

Local communities express frustration at perceived government inaction. Despite studies showing the dangers of these networks, awareness campaigns and financial support are lacking.

“The government tells us ‘start small businesses, sell something, you will succeed’ — but where is the finance? Where is the space? Where is the safety?” asked one local.

The testimonies highlight structural governance failures: weak security, limited protection, and a lack of economic opportunities. These gaps continue to drive a migration crisis that threatens both the social fabric and the future of Tigray’s youth.

Three weeks ago, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) reported that a vessel carrying 157 people had sunk in the Gulf of Aden.

The disaster took place near the coast of Abyan governorate—an area often used by smugglers moving migrants from East Africa to Gulf States like Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. The families of the youth who migrate using this route remain in a constant state of fear in Tigray, still unsure whether or not one of their sons, daughters, brothers, sisters, or neighbors were among those lost in the disaster.

Other developments closer to home only add to their worries.

In December 2024 the Tigray Youth Association (TYA) reported that a conflict-borne power vacuum has enabled criminal networks to operate with impunity and exploit vulnerable individuals, often luring them with false promises of employment and a better life.

The networks recruit young people and facilitate their movement along dangerous migration routes that span Tigray, Eritrea, and Sudan, according to the Association.

TYA, in collaboration with the German embassy in Addis Ababa, conducted a comprehensive field assessment across the Tigray region.

The findings revealed that 40 percent of youth in the region expressed an interest in pursuing migration routes. Additionally, youth mobility was recorded at 54 percent, encompassing movement within the Tigray region, other parts of Ethiopia, and beyond the country’s borders.

In the region, 53 percent of the approximate 2.4 million youths aged between 29 to 35 are already displaced, according to the assessment.

A related ground survey, based on a recent IOM report, indicates a significant increase in human trafficking and illegal migration in the Tigray region.

Excluding Mekelle, the survey found that more than 32,500 youths from six zones migrated using various routes during the previous Ethiopian year 2016. Additionally, the TYB assessment identified the Southeastern Zone of Tigray as having the highest migration numbers at 1,830.

The assessment also revealed that 13,229 youths returned from migration during the same period.

The survey recorded a total of 300 deaths among the 6,000 youths who fled the country since the start of the 2017 Ethiopian year.

.

.

.

#Losing #Generation #Tigray #Faces #Deepening #Crisis #Displacement #Trafficking #Political #Turmoil

Source link