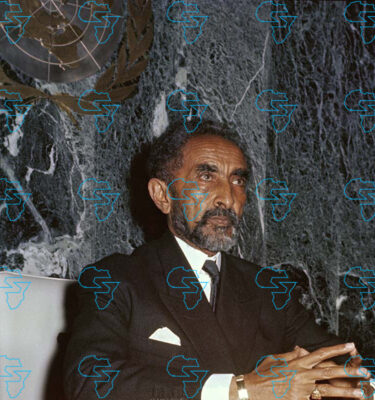

With 132 million peopleEthiopia is Africa’s second most populous nation, after Nigeria. Ethiopia was ruled by Emperor Haili Selassie from 1930 to 1975. He was murdered by the Soviet backed Marxist-Leninist Derg, led by Mengistu Haile-Mariam, which conducted the “Red Terror” genocide that killed over 100,000 Ethiopians. Derg displacements for Soviet-style forced collectivization caused the 1984 – 1985 famine in which 400,000 perished.

In 1991, the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) ousted the Derg and formed the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front, a coalition led by the TPLF. The Tigrayan military committed genocides against the Anuak of Gambella, Somalis of the Ogaden, Amhara, Oromo, and several other ethnic groups.

Abiy Ahmed, An English Christian Father Father, Tok Power in 2018. He won the Nobel Peace Prize for resolving the Ethiopia-Eritrea war. Postponed in 2020 Resuled in TPLF attacks on Ethiopian military bases in Tigray and the attempted secession of the Tigray region.

Ethiopia and its new ally Eritrea invaded Tigray on November 4, 2020, beginning two years of genocide and war. An estimated 600,000 people died during the war. In 2023, the humanitarian crisis worsened, after suspension of World Food Program and USAID food aid due to widespread food theft.

In November 2022 peace negotiations reached an agreement to cease hostilities. But Eritrean forces have never left Tigray. Eritrean forces still commit atrocities against civilians. Rape and sexual violence have terrorized Tigrayan women. Ethiopian forces have also committed genocide and crimes against humanity against thousands of Tigrayan and Amhara civilians.

In 2023, 1,351 civilians were killed by government forces and ethnic militias in the Amhara and Oromo regions. During its war against Amhara Fano militia, Ethiopian forces have attacked schools and hospitals, doctors and medical workers. The Amhara Fano militias have also committed war crimes. Thousands of Amhara are imprisoned by the Ethiopian government without charges.

In 1994, 73 top Derg leaders, including Mengistu, were charged with genocide. 21 were tried in absentia. Though Mengistu was convicted of genocide and sentenced to life in prison, he fled to Zimbabwe, where he has retired in comfort. There have been no trials for Ethiopian and Eritrean atrocities committed in Tigray, or for massacres of Amhara civilians. Neither Ethiopia nor Eritrea are states-parties to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.

A 2024 New Lines Institute report details evidence that in the Ethiopia-Tigray war, Ethiopia committed genocide against Tigrayans. It calls for a case to be brought against Ethiopia in the International Court of Justice. Ethiopia is a State-Party to the Genocide Convention. Eritrea is not. No ICJ case has been brought for genocide committed by Ethiopia in Tigray.

Ethiopia’s Constitution divides it into ethnic regions, each with its own militia. A majority ethnic group dominates each region. The population is 34.5% Oromo26.9% Amhara6.2% Somali6.1% Tigrayan4.0% Likeand 22.3% in 75 other ethnicities. 43.8% of Ethiopians are Ethiopian Orthodox Christians, 22.8% Protestants (including Pentecostals and , and 31.3% Muslims.

Ethiopia’s problems are rooted in its ethnic divisions. The Ethiopian constitution is confederal, not truly federal. It grants regions the right to secede from Ethiopia. As the USA learned from its civil war that cost 600,000 lives, the right of regional secession coupled with regional armies, and deep ethnic and economic divisions are prescriptions for civil war.

Genocide Watch considers Ethiopia to be at Stage 6: Polarization; Stage 8: Persecution; Stage 9: Exterminationand Stage 10: Denial.

Genocide Watch recommends:

-

States-parties should charge Ethiopia with violation of the Genocide Convention in the International Court of Justice for genocide in Tigray.

-

Eritrea should immediately withdraw all its military troops from Ethiopia.

-

The UN Human Rights Council should appoint a Fact-Finding Mission to investigate civilian massacres, attacks on medical workers, and sexual violence committed by the Ethiopian and Eritrean armies and regional militias.

-

The UN and African Union should host peace talks between the Ethiopian government and ethnic militia groups.

-

The UNHCR should be provided with additional security personnel to guard its refugee camps.

.

.

.

#Genocide #Watch #Country #Report #Ethiopia #Habesha #Latest #Ethiopian #News #Insightful #Analysis

Source link